WHEN REALITY BECOMES FICTION: ON THE OPPOSITE SIDE OF GEOPOLITICS AND HEALTH IN TIMES OF THE PANDEMIC IN BRAZIL

Posted on

July 2, 2020

By: Anne Dorothée Slovic, PhD Professor and researcher of the SALURBAL project - University of Sao Paulo

Lídia Maria de Oliveira Morais, Biologist, master in Sustainable Development and researcher of the SALURBAL project at the Urban Health Observatory of Belo Horizonte OSUBH-Federal University of Minas Gerais

José Firmino de Sousa, researcher of the Salurbal project, Fiocruz Salvador

Waleska Teixeira Caiaffa, SALURBAL project researcher, MD, PhD, MPH

One of the most famous Brazilian songs, composed by Jorge Ben Jor, refers to Brazil as “a tropical country, blessed by God and beautiful by nature”. However, behind all this tropical beauty (or what remains of it), there is a country where social inequalities, precarious access to health, violence, corruption and the struggle for power remind us of the sad reality experienced by the vast majority of its population. This is particularly true in Brazilian cities where the phenomenon of urbanization is marked by work instability and the rise of an informal economy that adds to the problem. For decades, Brazilian cities have faced a lack of basic sanitation, segregation, and precarious housing. In the context of the pandemic, these age-old problems end up becoming more evident, especially regarding the resilience of the most vulnerable population and the competence of their leaders in coping with the disease.

THE BITTERNESS OF THE TROPICAL COUNTRY

Picture: Anne Dorothée Slovic

Much has been said about COVID-19 and the consequences of the pandemic: measures of social isolation, quarantine, lockdown, banning trade, remote work, economic recession, saturation of health services, loss of family and friends, mourning for people and the way of life we all used to have. In the case of Brazil, this situation is aggravated by the current state of affairs: chaotic politics, with successive contradictions between leaders in orienting the population, a neoliberal economy that is scrapped and in full recession, fragile institutions and vicious cycles of ideological character where any articulated attempt at organization at the national level to fight the epidemic is boycotted. With the imminence of the next municipal elections, the political dispute between mayors of the main cities of the country, governors and the Presidency of the Republic is felt in the streets, in the attitudes of the population, in the difficulty in establishing measures to fight the illness and in the exaltation of the false dichotomy between health and economy. The aggravating of fake news, a phenomenon called “infodemia” by the World Health Organization, adds to this scenario confusing the population and inducing ignorance and panic about the disease and the necessary care.

Much has been said about COVID-19 and the consequences of the pandemic: measures of social isolation, quarantine, lockdown, banning trade, remote work, economic recession, saturation of health services, loss of family and friends, mourning for people and the way of life we all used to have. In the case of Brazil, this situation is aggravated by the current state of affairs: chaotic politics, with successive contradictions between leaders in orienting the population, a neoliberal economy that is scrapped and in full recession, fragile institutions and vicious cycles of ideological character where any articulated attempt at organization at the national level to fight the epidemic is boycotted. With the imminence of the next municipal elections, the political dispute between mayors of the main cities of the country, governors and the Presidency of the Republic is felt in the streets, in the attitudes of the population, in the difficulty in establishing measures to fight the illness and in the exaltation of the false dichotomy between health and economy. The aggravating of fake news, a phenomenon called “infodemia” by the World Health Organization, adds to this scenario confusing the population and inducing ignorance and panic about the disease and the necessary care.

All over the world, the effects of social isolation and the closing of shops and services are being experienced in a very different way depending on socioeconomic status as well as living and working conditions. In Brazil, this factor is accentuated considering that we live in one of the most unequal countries on the planet. Here, misery remains, and a large portion of the urban population lives in precarious conditions on the margins of society in informal settlements “favelas” without adequate sanitary and structural conditions for a decent life. What about the prospect of taking the necessary steps to stem the spread of the virus? With more than 610,000 known cases, less than four months after the first case was officially reported in early June, Brazil reported more than 34,000 deaths and a mere 986,000 tests performede .

Public hospitals in several capitals lived and are living through critical moments, lacking beds in the Intensive Care Units (ICUs) in the Northern capitals of Manaus and Belém. With the spread of the virus and rise of the number of cases in the country, the situation tends to replicate in other cities. In some of the main capitals of the country, such as São Paulo, Salvador, Rio de Janeiro and Belo Horizonte, city halls adopted several measures to face COVID-19, implemented from the first half of March. Since the beginning of the epidemic, the State and the city of São Paulo quickly became the epicenter of the cases, followed by this escalation in Rio de Janeiro. Cities like Manaus, Recife and Belém, however, were the first to face chaos in health systems and in the way of dealing with their deceased. Belo Horizonte, Porto Alegre and Salvador, on the other hand, have shown themselves to be more diligent in controlling the spread of the disease. Still, they are faced with underreporting of cases. These places, despite the epidemic continuing to progress in number of cases and deaths, are still considered capable of care by the Unified Health System (SUS). Emphasizing how the SUS has bravely demonstrated its importance despite the negligible volume of investments experienced in recent years. The figure below shows images of field hospitals built, mostly, with SUS resources.

Field hospitals in Brazil

Foto: Google Images

SPREAD AND MARGINALIZATION OF THE EPIDEMIC

In Brazil, the situation in urbanized areas is serious and unstable and the greatest challenge has presented itself at the time the pandemic has spread to the outskirts of major capitals. The portion of the Brazilian population in the worst socioeconomic conditions is faced with the dilemma between continuing to work to survive and being exposed to possible contagion in precarious and informal workplaces, public transport, housing and neighborhoods without sanitation and hygiene conditions. In addition, access to health services is unstable the more peripherally positioned these populations are physically, socially and economically.

Traditional peoples and communities such as the indigenous communities and quilombolas suffer the consequences of these processes. Manaus, the capital, and the only city in the state of Amazonas with ICU beds equipped with respirators, receives a contingent of populations of many indigenous ethnicities who travel distances unthinkable for any emergency care professional. This situation is repeated to a lesser extent in any rural context in which small communities rely on nearby urban centers for more complex medical care, funneling through to the capitals the more critical the health need is. The spread of the disease has repercussions in large urban centers with an exponential potential of contagion in peripheral and poorer regions. This is a time bomb for health systems.

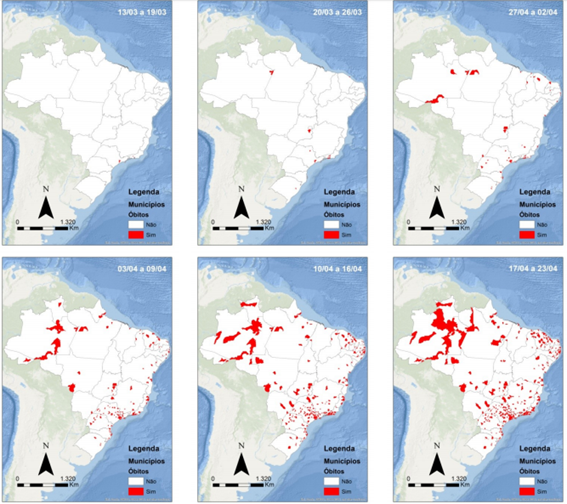

The Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FioCruz) and its Health Information Laboratory (LIS) launched “MonitoraCovid-19”, an information system open to the public for monitoring the pandemic. The reports prepared by the Monitor COVID-19 also allow to observe the accentuated process of spread and tropicalization of the disease and deaths caused by the virus, as shown in the maps below.

COVID-19 Movement towards inland Brazil between March 13th and April 23rd, 2020

Source: Boletim MonitoraCovid-19

INFORMATION AND TRANSPARENCY

The lack of standardization in the dissemination of results is a challenge for reliable and consolidated analyses. The State Central Public Health Laboratories (LACEN), the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FioCruz) and the Butantan Institute (in the state of São Paulo) are the reference institutions for carrying out molecular tests and disseminating the COVID-19 test results, since the Ministry of Health positions itself in a subservient manner to the political interests of the presidency of the Republic and has been boycotting the dissemination and transparency of data at national level. Mass testing of the Brazilian population, therefore, is not yet possible. Health and safety professionals, other professionals who work to cope with the disease and their families have been a priority in the tests, and some incipient serological research with rapid tests performed by these and other institutions have also been observed.

Transparency in the data becomes essential for the efficient fight of the disease. However, the lack of communication and coordination between the municipal, state, and Federal spheres has been a major challenge. States and municipalities have considerably increased the performance of molecular tests and rapid tests, which facilitates the monitoring of the evolution of COVID-19. However, the lack of support from the federal level makes it difficult to standardize the communication of cases and allows discrepancies between the official numbers announced at the national level and the official numbers announced by the state departments. In the first week of June, the Federal Government announced that it would adopt a new methodology for counting notifications of infections and the number of deaths by COVID-19. The methodological break was viewed with suspicion by health organizations throughout Brazil, in addition to having international repercussions. The Brazilian press formed a consortium to keep the population informed about the number of cases and deaths based on data from the state health departments. The National Congress is also articulating for the construction of a disease monitoring that brings reliability to the Brazilian data.

ECONOMY AND HEALTH

The effects of COVID-19 on people's lives, society and the economy are devastating. The World Bank already estimates the drop of 8% of the Brazilian GDP in 2020. To mitigate the effects of the disease on the population's income, Bill 9236/2017 was approved by the National Congress at the end of March, establishing the payment of aid emergency of R $ 600.00 for three months for families in the informal work sector, and if the family is a single parent, the benefit is even higher at R $ 1,200.00, also for a period of three months. According to the scenarios projected by the Government, PL 9236/2017, transformed into Ordinary Law 13982/2020, can serve up to 36.4 million families or 117.5 million individuals, equivalent to 55% of the Brazilian population, and would have an estimated cost of R$ 99.6 billion.

To facilitate the granting of credit to medium and small companies, as well as to individuals, the government estimates to release R $ 1.2 trillion for banks. Other actions in the financial sphere allow banks to borrow from the Brazilian Central Bank in amounts of up to R $ 68 billion. Such measures aim to ensure jobs and the permanence of small and medium-sized companies in the market. The question that arises is whether, in fact, banks are willing to take "responsibility" for active activity in the economy or prefer to maintain their profit margins.

The false dichotomy between health and the economy needs to be cut out. There is no wealth and income without a healthy and willing population to work. Essential economic sectors such as supermarkets, pharmacies and others must continue to function to guarantee supplies and meet the basic needs of the population. However, the momentary interruption of other non-essential activities is vital to flatten the virus transmission curve and enable the Unified Health System (SUS) to save many lives. In the case of Brazil, it was evident the essential contribution of governors and mayors who, depending on the state and their local conditions, have been facing the disease without support from the Federal Government. What keeps Brazil going today is not its president, but the local governments that have taken more rigid stances in relation to social distancing and leading the fight this generalized crisis. With the number of cases and deaths due to COVID-19 increasing in Brazil, the precarious attempts at “quarantining” differ between states and municipalities and are worthy of a fictional horror film where many lives will be lost.